Gleams from Dyce Head Light Save Pilot and Launch a Christmas Tradition

Flying Santa! In lighthouse and Coast Guard circles, the mere mention of the name brings a joyful smile to many a face. For the Flying Santa is a classic tradition that is still gifting novel holiday cheer to the families of seaborne guardians.

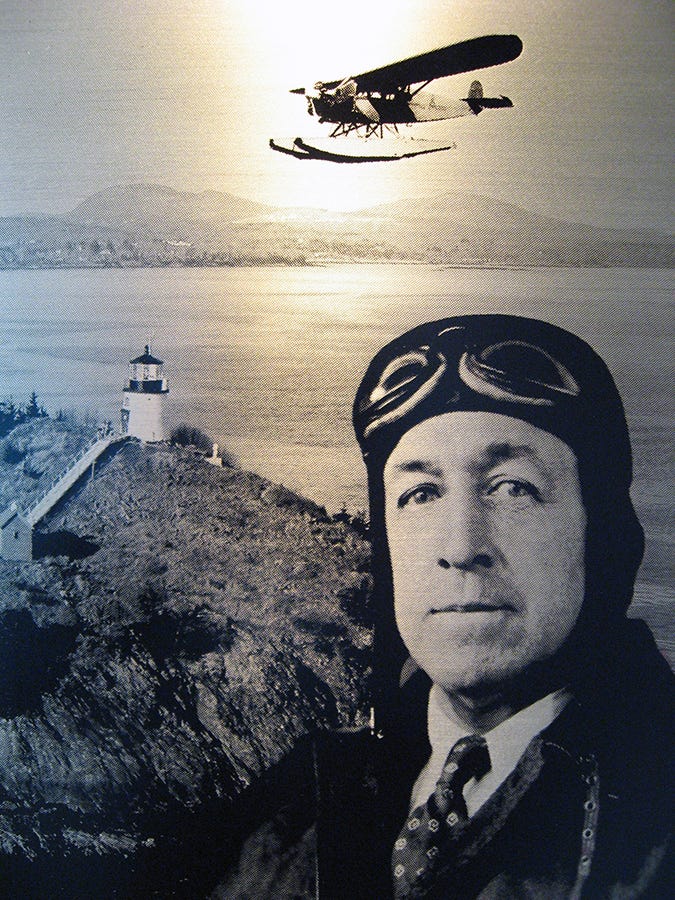

Captain William H. Wincapaw started this near century-old tradition in 1929. The story that sparked this annual mission is as extraordinary as the Flying Santa’s renowned history of delivering gifts at Christmastime.

Before the personage of the Flying Santa ascended to lofty heights, the legend of Captain William Wincapaw was widely acclaimed along the Maine coast and beyond. A 1933 Boston Evening Transcript aviation column captured the profound impact of Captain Wincapaw’s on coastal communities and aviation in general.

According to the Boston Evening Transcript, “William H. Wincapaw, or Captain Bill they call him way down in Maine. He is to aviation at Rockland what the whaling boat skippers were to New Bedford in the days of the ancient mariner. Mr. Wincapaw is aged and mellow in experience and modern in his ideas and customs.”

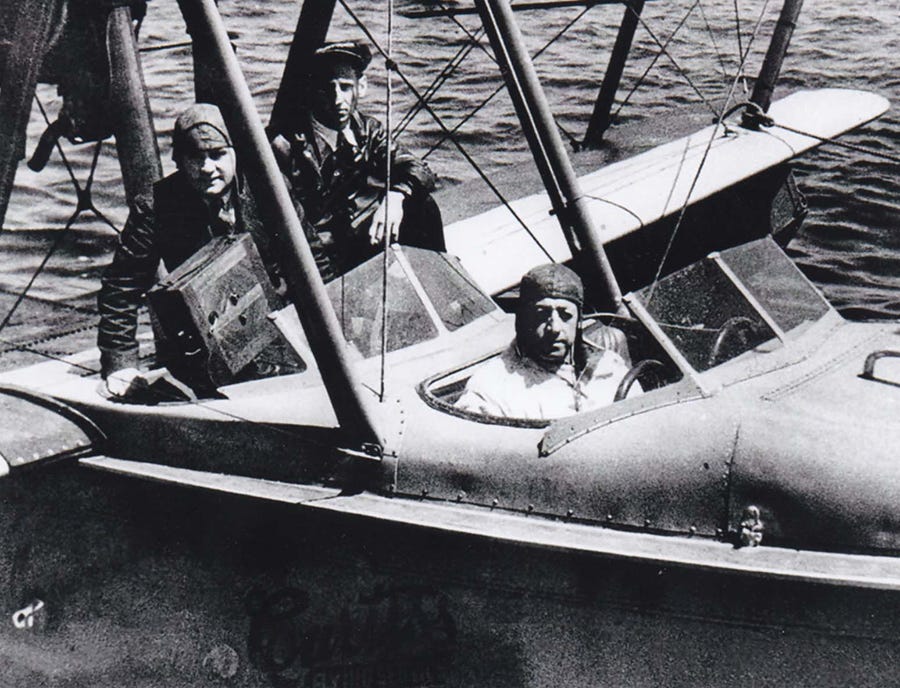

The newspaper went on to note, “There are few people who have used the airplane for the sake of humanity more than Captain Bill. He has flown seaplanes through raging storms and landed between towering waves at night to take people from islands near Rockland to the mainland for emergency operations. More than one person owes his life to speedy action by Bill Wincapaw.”

The Boston Evening Transcript was not exaggerating when it stated that the famed pilot flew through “raging storms.” In fact, the concept of Flying Santa was born out of a wing and a prayer during the Great Sleet Storm of December 18 & 19, 1929.

Whether Captain Wincapaw took off from Rockland’s Curtiss-Wright airfield amidst the storm or became caught in its grasp on his return trip home, is not known. What is known is that the storm nearly cost the pilot his life.

The winter storm itself was no ordinary weather event. Far from it!

Along the Maine coast on December 18 & 19, 1929, ice was weighing heavy on trees, causing damage and widespread power outages. In the wake of the sleet storm, the Rockland Courier Gazette noted, “During the past sleet storm, ice formed quickly on tree limbs, dropping them straight downward.”

But how severe was the 1929 sleet storm? For those who remember the Great Ice Storm of January 1998, the 1929 storm was comparable.

An April 1998 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers report entitled, An Evaluation of the Severity of the January 1998 Ice Storm in Northern New England, Report for FEMA Region 1, draws the comparison to the two storms, stating, “The January storm is not without precedent. Sixty-eight years ago, in December of 1929, an ice storm that extended from western New York into Maine caused tree and overhead line damage comparable to that in this storm.”

Now imagine flying in this type of ice storm? It is common for ice to accrete on the external parts of an aircraft, including the wings, during such weather events. This is exactly what was happening to Captain Wincapaw’s seaplane as he flew back to Rockland amid little to no visibility following the delivery of mail and supplies to various outposts in Penobscot Bay.

No doubt Captain Wincapaw leaned on every ounce of his experience, well-honed skills and extensive knowledge of the bay during his harrowing flight through the storm – and yet, it was nearly not enough.

A feature entitled, Lighthouses – Christmas Tradition Began with Lost Airplane Pilot, describes the predicament, saying, “It was the week before Christmas in 1929 and William Wincapaw of Rockland, Maine, was lost in a snowstorm off the Maine coast, running low on both fuel and hope. Desperately, the cargo pilot circled his plane above the gale-lashed waters of Penobscot Bay and glimpsed light blinking through the snow – the Dyce Head Lighthouse.”

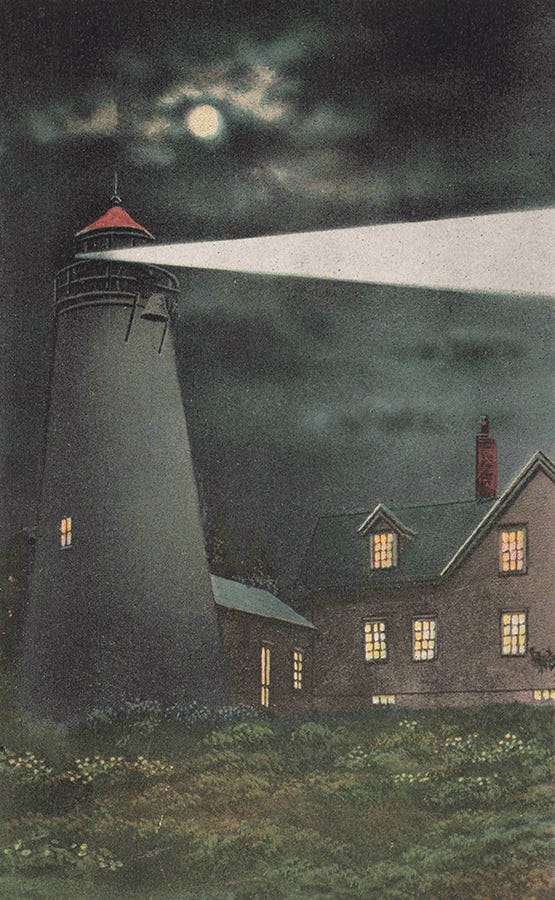

Dyce Head, the venerable sentinel of the historic Town of Castine, Maine! This 1828 guardian has long guided mariners along the upper reaches of Penobscot bay, while beckoning summer visitors to linger and listen closely for echoes of grand maritime days gone by.

However, despite its rich history, Dyce Head Lighthouse does not possess the storm and shipwreck drama associated with Maine’s remote or wave-swept sentinels. By comparison, Dyce Head was more of an idyllic sentinel whose quietude was deep, especially during wintertime.

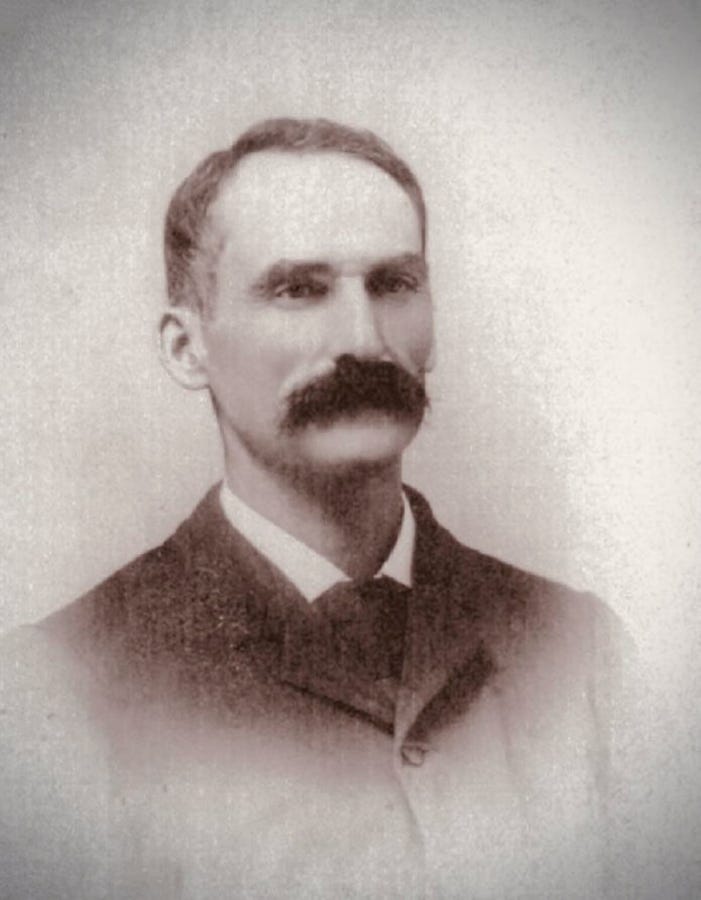

A January 1932 letter by keeper Vurney L. King captures the tranquil essence of Dyce Head Lighthouse. “This station, being so far inland, we do not see so much happen as the offshore stations,” said Keeper King. “Traffic in navigation by this station is very small at this time of year, only a few steamers loaded with pulp wood and coasters with lumber or wood. Routine work such as keeping the light going, cleaning brass, stoking the fires and touching up with paint occupies our time these short days.”

“Keeping the light going.”

Keeper Vurney L. King could not have possibly known just how strangely important this routine task would prove to be on the night of December 18, 1929. If his beacon aglow was going to be of any hope and guidance to someone coping with the fury of the gale, he most certainly would have thought it upon jostled waters – not in the air.

On this night – as on any other night, Keeper King ensured the beautiful 1858 fourth order Fresnel lens in the lantern of Dyce Head Light was shining bright before settling in for the evening.

What occurred thereafter was impossible to have imagined, and it remains unknown as to whether Keeper King ever heard the engine noise from Captain Wincapaw’s seaplane amidst the din of the storm as the aircraft flew by. During his time at Dyce Head Light Station, Keeper King had noted, “We feel no gales at this station, and being up in the bay so far, our only inconvenience is shoveling snow.”

Speaking of Captain Wincapaw, can you imagine the anxiety racing through his mind as the seaplane accumulated ice and was running low on fuel? He had to ponder the possibility of a worst case scenario – having to land the aircraft in the dark, upon the storm-tossed waters of Penobscot Bay.

Would anyone see him if he had to bring the aircraft down? Could a rescue be effected? Would the seaplane stay afloat amid rough seas for very long? And of course, would he himself survive the ordeal?

Thankfully, these questions never had to be answered. For through the shroud of night and storm came a beam of hope – steady, white and duly intent on showing the way to safety.

In 1999, Ken Black, founder of the Maine Lighthouse Museum in Rockland, stated, “He kept flying lower and lower until he spotted the beam of Dyce Head Light. Using this as his landmark, he was able to set a safe course for home by following the beams of six other lighthouses.”

By following the gleams of Penobscot Bay’s lighthouses, and holding fast to his determined spirit and talents, Captain Wincapaw was able to make it back to the Curtiss-Wright airfield in Rockland – running out of fuel on the runway! As the Boston Evening Transcript said, “Ole Bill himself is what his fellow pilots call a ‘darn smooth flyer.”

Be it fixed or flashing, a single ray of light can make all the difference in someone’s hour of need. It is only a dissipating flash until the light saves a life. Then the guiding gleam is crowned in the glory of heroism and destined to burn bright forevermore in the hearts and minds of those saved from mishap or catastrophe.

Captain William H. Wincapaw no doubt remembered the first instant he espied the light at Dyce Head for the remainder of his life – all because keeper Vurney L. King was vigilant with a task the ‘wickie’ deemed routine.

To show his heartfelt appreciation for the help lighthouses provided during his flight in the December 1929 sleet storm, Captain Wincapaw assembled and wrapped a dozen packages for lightkeepers. He took to the sky a week later on Christmas Day 1929 and dropped the gifts on the lawns of Penobscot Bay light stations, including Dyce Head Light.

With that, the Flying Santa tradition was born!

Captain Wincapaw would continue the Christmastime flights in the years that followed before passing the torch to New England’s renowned maritime author, Edward Rowe Snow.

Thereafter, Mr. Snow would serve as the Flying Santa for over forty years. Today, the tradition continues to shine bright thanks to the amazing efforts of the nonprofit Friends of Flying Santa, led by their indomitable president, Brian Tague.

As for Dyce Head Light’s keeper Vurney L. King, he is the unsung hero of this Christmastime tradition. The veteran wickie is a testament to the fact that heroism is not rooted solely by acting amid extraordinary circumstances – but ordinary ones too. One pilot, one keeper and one light — an amazing story that endures and shines on, nearly a century later. Merry Christmas!

What a wonderful story. Thank you for telling this history.

I enjoyed reading this. Certainly another look at the guiding light. And for flying Santa.