A Storm for the Ages at Matinicus Rock Light

Today – November 26, 2024, marks the 74th anniversary of the epic storm that struck Matinicus Rock Light Station on November 26, 1950 during Thanksgiving week.

I wrote this story in late 2019 and it was originally published in the January 2020 issue of Maine Lights Today magazine. I remain grateful to Steven Hiller, son of Matinicus Rock lightkeeper Stan Hiller, for sharing his father’s memories with me at the time.

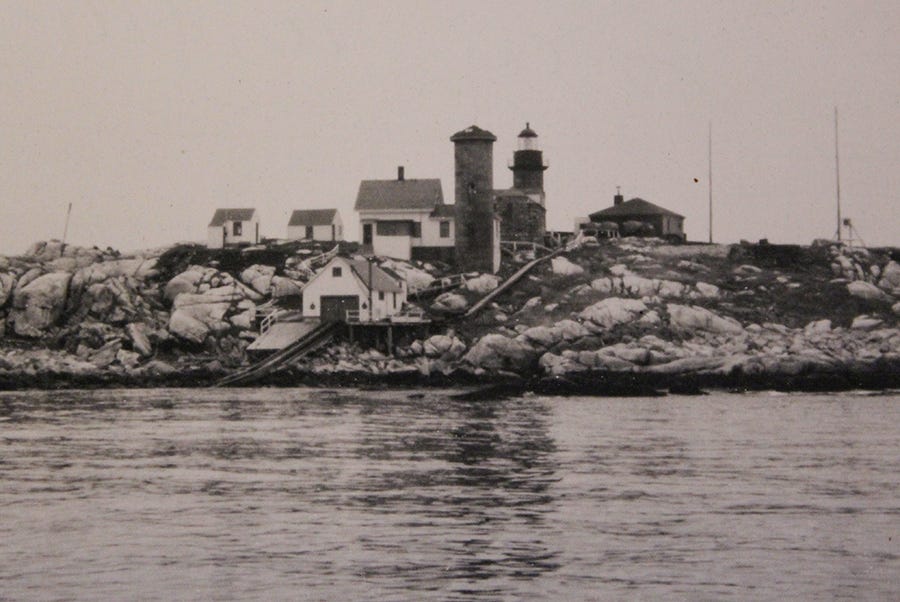

Matinicus Rock’s storied history is replete with accounts of great storms that have battered this remote offshore light station, which is located 27.5 miles southeast of Rockland.

During the most powerful tempests of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, seas have swept over the rock in harrowing fashion. In doing so, vast volumes of water damaged or carried away a number of the station’s outbuildings and seawalls – and threatened the very safety of those who kept the lights.

The roll-call of mighty storms at Matinicus Rock includes: 1839, 1842, 1856, 1878, 1888 and 1933, among other notable tempests in the annals of the station. In the wake of each of these storms, it was impossible to land a boat at the island for days – and sometimes for weeks on end.

However, there is one gale that stands out in history at Matinicus Rock as being both strong and unusual. This particular storm swept over the 32-acre island on November 26, 1950, and would go on to become known in meteorological circles as the Great Appalachian Storm of Thanksgiving Week 1950.

A manic southeast wind was the driving force behind the chaos that stirred the air and sea to a frenzy during the storm – creating quite a dire situation for the three keepers on duty at Matinicus Rock.

In his book, Extreme Weather; A Guide and Record Book, author Christopher C. Burt stated, “Known as the Great Appalachian Storm, it ranks as one of the most extreme, costliest, and anomalous extratropical storms in U.S. history.”

Burt was not alone in this opinion. Distinguished meteorologists Paul Kocin and Louis Uccellini noted in their authoritative volume, Northeast Snowstorms, “Although this is not a traditional ‘Northeast snowstorm’, since the heaviest snows fell far west of the Northeast coastline, it is included here (in our book) because it represents perhaps the greatest combination of extreme atmospheric elements ever seen in the eastern United States. We feel that this storm is the benchmark against which all other major storms of the 20th century could be compared.”

Finally, meteorologist Ryan Hanrahan stated, “For a non-tropical storm there’s no question in my mind that the 1950 southeaster was the most violent windstorm we’ve seen.”

There was an extreme pressure gradient with this storm, resulting in devastating winds up and down the Atlantic seaboard. “The unseasonably warm weather, when coupled with a ripping low level jet, led to enough turbulent mixing to mix down destructive winds – in some cases to 100 mph,” noted Ryan Hanrahan.

The storm’s magnitude proved far greater than the Coast Guard keepers on duty – Acting Officer-in-Charge, Engineman 3rd class Stanley Hiller, Seaman Arthur Gould and Seaman Apprentice Jack Battle, could have ever anticipated. Chief Harry “Salty” Waters, Officer-in-Charge at the light station, was on leave at the time when the gale struck.

Storm winds raged and ripped things apart on Matinicus Rock. Beyond the physical damage to station buildings, the tempest’s incessant howl had to be as equally unnerving for the keepers – spawning an inescapable aura of uncertainty in their minds as to what might come next. No doubt the wind sounded like a nonstop freight train for hours on end as it drove rain and seawater into every nook and cranny of the light station structures.

However, buffeting winds were not the only concern of the keepers. At the height of the storm, the fury of the sea was running unabated. Thunderous waves were pounding the Rock and washing completely across the island.

The crew eventually determined that it was unsafe to remain inside the wooden keeper’s house, which was located near the decommissioned north tower. Two feet of seawater flooded the interior and winds threatened to inflict serious structural damage. As keeper Stanley Hiller noted, the dwelling “shipped water, continually, making it impossible for the crew to remain.”

The time had come for the keepers to relocate to the 1846 granite keeper’s house, which was no longer used, but did house emergency rations, supplies, etc. The old dwelling was sturdy and represented the best option at hand for the three keepers. That said, the dwelling’s roof did end up suffering damage during the storm, and various windows were blown out. The shattered windows forced the crew to move from room to room in an effort to try and remain dry.

As fate would have it, radio communication was also lost. Keepers Hiller, Gould and Battle were unable to alert the Coast Guard base in Rockland as to their dreadful plight – not that it would have mattered. No help could reach the Rock under such furious storm conditions. Regardless of what happened, the keepers were on their own.

While the crew tried to hunker down in the century-old house and stay out of harm’s way, outside, things were going to pieces – literally. The wind and sea had gone mad, earmarking much for destruction on the Rock.

Heavy seas battered the northeast seawall until the timber structure finally gave way. With a barrier no longer in place between it and the light station outbuildings, mighty waves swept the island unrestrained.

The hoisting engine house for the tramway car was subsequently wrecked – and shortly thereafter, seas pummeled the brick whistle house, which housed the machinery that generated power for the light, fog signal and radio beacon. The structure’s northeast wall fell under the battering.

While big seas pounded the whistle house, destructive winds knocked down the chimney, ripped off the roof and blew out the windows. At this point, the station’s main navigational equipment was no longer operational.

In addition, the long covered walkway that extended from the wooden keeper’s house near the decommissioned north tower to the operating south tower was utterly destroyed during the storm. Other station outbuildings fared no better. As renowned maritime historian Edward Rowe Snow would later say, “When I passed over on my Flying Santa journeys three weeks later, I was amazed at the destruction the ocean’s fury had accomplished.”

Though keepers Hiller, Gould and Battle could do nothing about the destruction happening around them, they did not forsake their lighthouse duties. When the main light – a third order Fresnel lens, stopped working due to the wrecked machinery in the whistle house, the crew went topside in the tower to illuminate the stand-by kerosene lamp, which was to be placed inside the lens as a backup light source.

However, when the keepers reached the lantern, they found a shattered mess. Seven of the heavy lantern panes were gone – blown out by a combination of the wind and sea. Waves were sending spray completely over top of the lighthouse – a scary thought given the beacon’s focal plane was 90-feet above sea level. One news report stated that sea spray was reaching a height of 107-feet at the Rock.

With wind, rain and sea spray ripping through the exposed lantern, the crew was unable to keep the kerosene lamp lit. Days later, The Boston Globe stated, “The light was doused to darkness for the first time in years.”

Lantern glass is thick and not easily broken during storms. The fact that seven panes were lost during the 1950 storm is almost unprecedented. During most every storm throughout the history of Matinicus Rock, keepers were able to keep the light burning despite the fearful seas and winds that assaulted the island.

However, a similar circumstance did occur at Matinicus Rock one hundred and eleven years prior to 1950. Lighthouse historian Jeremy D’Entremont notes, “A tremendous storm in January 1839 did much damage to the buildings and put the lights out of operation. Two days later, the keeper was able to hang a temporary lamp from a mast.”

Keeper’s Hiller, Gould and Battle were just as resourceful. One day later, the intrepid crew took old storm windows that were in storage and placed them around the lantern – using rope to secure the make-shift arrangement. The November 30, 1950 edition of The Boston Globe noted, “Coast Guardsmen rigged an emergency light in the tower of the island lighthouse. Last night that light was flashing a feeble beam seaward. Matinicus was no longer darkened.”

The resourcefulness of the keepers did not end with establishing a light back in the tower. They also needed to repair the radio and reestablish communications with the Coast Guard base in Rockland. The crew was anxious to report in and relay the fact that Matinicus Rock Light Station was in shambles after the storm had run its destructive course.

On November 27th, the keepers were able to overhaul the radio enough to get a weak signal out and report that they were alive, safe and using emergency rations to live on. The crew also informed their superiors that they were forced to drink distilled water intended for batteries since the station’s cistern was filled with salt water.

Despite learning of the emergency situation on Matinicus Rock, the Coast Guard was unable to safely land anyone at the island until five days after the storm when Chief Harry “Salty” Waters, the station’s Officer-in-Charge, and a fellow Coastguardsman tasked with assessing the damage, managed with great difficulty get aboard the Rock.

However, Captain William B. Chiswell, Chief, Aids to Navigation, First Coast Guard District, Boston, and other USCG personnel were unable to land at Matinicus Rock due to the rough conditions that persisted. So a decision was made to call in a helicopter from Salem Air Station. Captain Chiswell arrived at the offshore site on December 2, 1950 and wasted no time setting in motion all of the necessary procedures to ensure a rapid and thorough repair of the entire light station occurred.

Keepers Stanley Hiller, Arthur Gould and John Battle were fortunate to emerge unscathed from this terrible storm, especially given their location way out at sea. The Great Appalachian Storm of Thanksgiving Week 1950 impacted a very large area of the country and others were not as fortunate when it came to their lives.

“Somewhere between 160 and 353 people perished in the storm (depending on source), said Christopher C. Burt. “The insured damage costs reached $66.7 million in 1950 dollars, or about $680 million in 2018 dollars. This was the costliest storm of any kind (including hurricanes) for U.S. insurance companies at the time.”

For the three keepers at Matinicus Rock, it is certain that this powerful storm had a profound impact on their lives – something they would never forget. Without question, the 1950 southeast gale was a storm for the ages at Matinicus Rock.

The following letter by Matinicus Rock acting officer-in-charge Stanley Hiller describes the harrowing ordeal and subsequent repairs at the light station. The letter was published in the January 1951 edition of the Maine Coast Fisherman…

Inside Story from Matinicus

“Thanks for your kind thoughts and request for bits of news from the Ole Rock. Will try to meet your deadline.

“Well, to start out, this is a sad looking rock pile now, as the storm of 26 November did a job on the island. For those who have visited and served on this station, the covered passage way is completely blown away – 225 feet gone like the swing of the hatchetman in the woods, the main light lost seven panes of storm glass 77” x 33” x 1 ½” thickness, the light was out for a time and a makeshift light shown.

“No IOV light could be kept burning due to the force of the winds and rain. Next day old storm windows were roped all around the tower lens and the 300-watt lamp lighted up to dry out the lens. The drive motor was replaced with another from standby stock on hand and the light again flashed its helping hand to all who were coming home.

“The northeast breakwater wall was carried away and in turn stove in the hoisting-engine house and the machinery – thus the sea carried right on into the main whistle house and radio beacon signal house, battering down the northeast wall and part of the east wall, cleaning out the windows, chimney, roof, and tearing all over the place inside.

“All machinery was put out of commission, and the light failed; also the beacon and all communication equipment. The Ole Rock was sure taking a beating from the sea, as if the sea had planned just such a lesson to man for building a sea wall to keep the old sea from going wherever it wanted to.

“Hiller EN3 (L), Gould SN, and Battle SA, with old pal Towser, ship’s pup, departed from the main dwelling and took shelter in the old stone castle built in 1846 – and a shelter for many years in the past, taking care of its folks. Nothing could be done while the storm raged outside and everything was being moved off the island past the old silent castle built for just such a purpose as this – a challenge to the sea.

“The crew was safe and snug until the old windows started to let go and tear out. The sea and rain came in, and the boys moved from one room to another to keep out of the salt water and rain. Communication was cut off completely.

“On the 27th Hiller and the crew got a faint signal out to report all was well and things battered down badly. Fresh water was spoiled by sea water, and they were using the distilled water for drinking and boiling all cistern water for cooking. They were back in the dwelling and picking up housekeeping where they had left off, cleaning out sea water and dirt carried through the house and down into the cellar.

“Inspectors were standing by at Rockland moorings ready for landing conditions out at the Rock to get the story and make whatever recommendations for rebuilding immediately and installing equipment.

“December 1st, Salty and Turner got on the island after a rough time getting in close to the slip and then landing on the rocks a bit wet but ashore, fresh food with them. Turner immediately checked the conditions for his working party and ordered lumber and supplies.

“Commander Byrnes and Captain Chiswell arrived aboard the next day and things really got going in a short time with these men on the location and at the wheel. Nothing was overlooked. Pictures were taken and loads of equipment ready to come out from Boston and Portland bases and Rockland moorings. Things began to look up immediately after communication was put in, thanks to the ETM’s Billings, Grover, Soule radio calls. Had radiobeacon on the air from salvaged and cleaned apparatus, and the signals once again going out for those wanting them.

“In the engineer’s picture Doughty, Clifton T. and Hiller tore into generators, compressors, motors, air tanks and things began to take shape. The walls were patched and the beacon and light going, machinery was put into operation all drained of salt water and new fuel put in the tanks.

“The Snohomish arrived, bringing fresh water for the cistern, which had been drained and cleaned, 4,000 gallons of diesel fuel, and standby radio batteries. From the electrician’s department at Portland came head man Carns and Larabee electrician. Things got going with snap and crack when Carns got going with his meters. All wiring was tested out and the water-soaked shorted wiring cut out of the circuit-wall all were replaced.

“GC Laurel is now standing by at Rockland with a deck loaded with building and miscellaneous supplies for rebuilding the walls, new bank of batteries, and new radiobeacon equipment to be installed immediately.

“The working party men were Turnerm Adlof, Kimball and Blair. Thanks to them. They shingled with frozen fingers and frozen shingles to get the roof covered over to keep the rains from coming down on the only small part of the operating machinery and beacon. Then they departed for a well-earned holiday, making sure we who carried on were dry and patched up until the materials will arrive to rebuild.

“The grave crypt of Bessie Grant, buried at the age of three years in 1881, was spared washing out by the kindness of Edgar Wallace, former keeper before Salty came. As he re-cemented the walls around the quiet place where the baby rests, the seas passed by all around the grave.”

(Later)

“Sorry to have covered so much of the letter with storm damage, but questions are coming thick from our good friends and fishing boats. Some of the buildings will be missed by those who knew the island, but it’s the same.

“The Audubon group house was carried away completely and left down at the bottom of the island – just kindling size for the stove. Thus the end of the tiny Knotts Hotel, named for Wayne Knotts now at Mount Desert Rock Light Station. Sorry Knotts, nothing could have held the hotel or bar and grill that night. See you again soon. Bye now, must have my bones, Towser.”

Thank you for sharing this amazing story of the storm on Matinicus in 1950. I wasn't born yet, but my Mom was pregnant with me at that time in Rockland. I bet my grandfather, Ratio Cowan, would have remembered that storm well. He had a boat back then. It makes me wonder if that was the storm when it got destroyed in Rockland harbor. I'll have to check my old newspaper clippings. I remember my grandfather talking about Matinicus occasionally. Thank you so much for the story. It was fascinating.

Their dedication to seeing the light shine again amidst the destruction all around them, epitomizes the symbolism of hope a lighthouse gives.